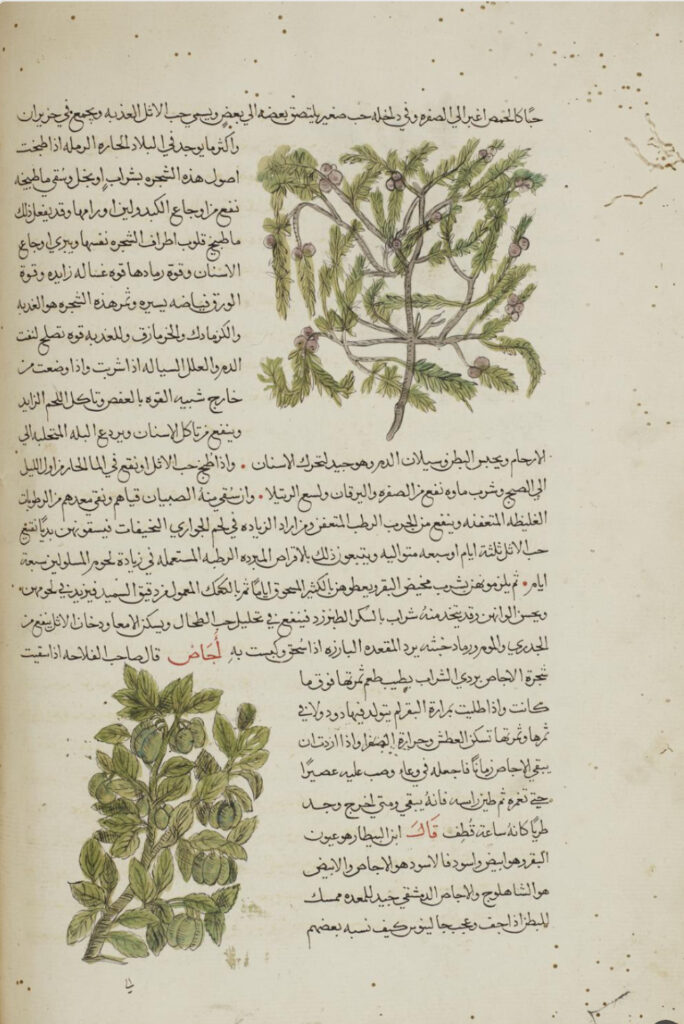

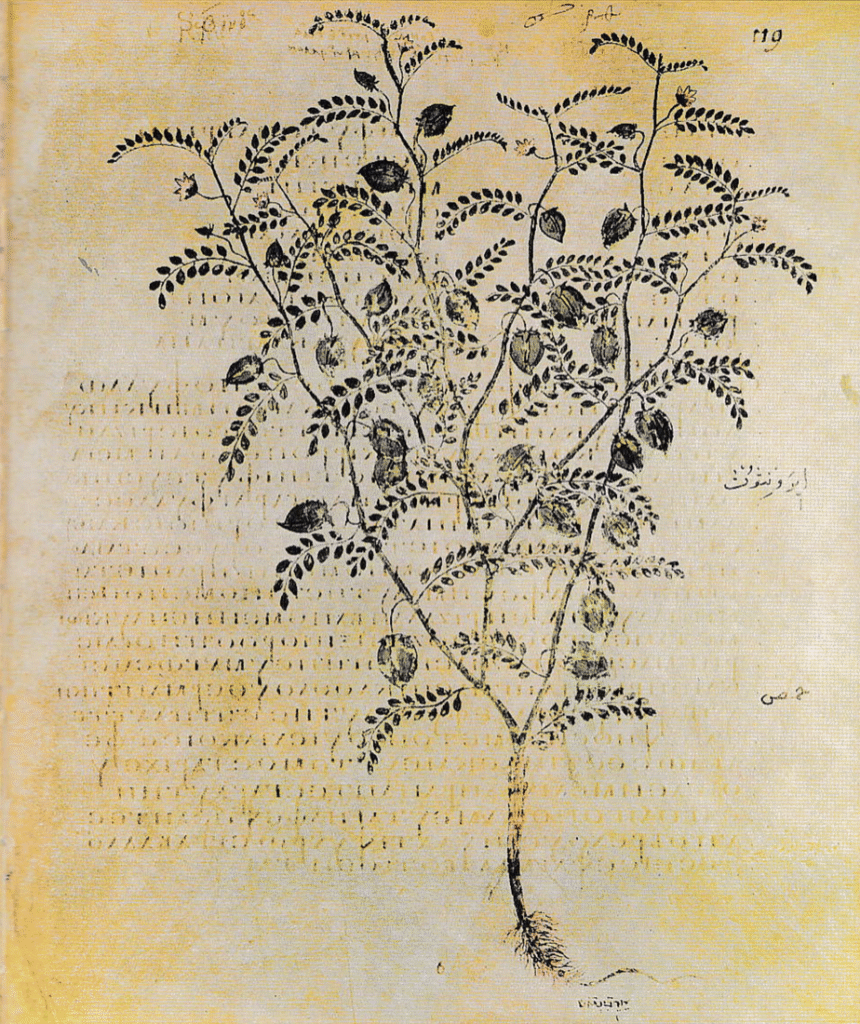

Both black (Morus nigra) and white mulberries (Morus alba) have Asian origins. The latter variety is primarily associated with China where it has been used in the production of silk as silkworms fed on mulberry leaves. The black mulberry, which is the one usually grown for food, hails from the same area or more West, in the Caucasus or Anatolia. In ancient Greece, it was already eaten fresh or preserved, with Galen pointing out that it cannot be dried. There are a few scanty Greek references to a mulberry sauce with fish, but it does not appear as an ingredient in Apicius’ recipe book.

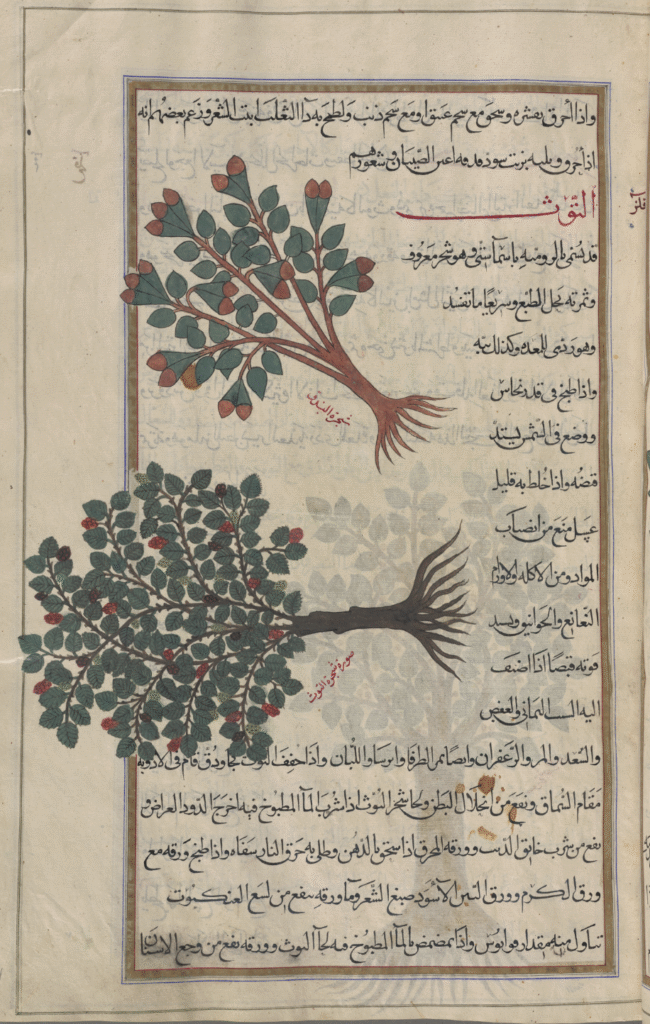

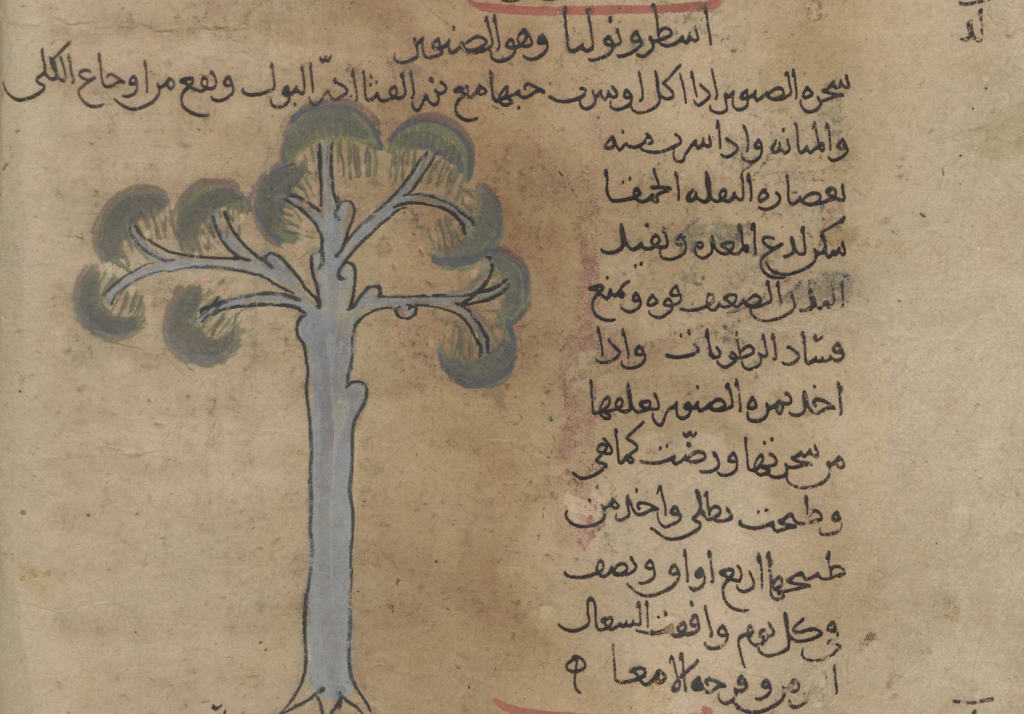

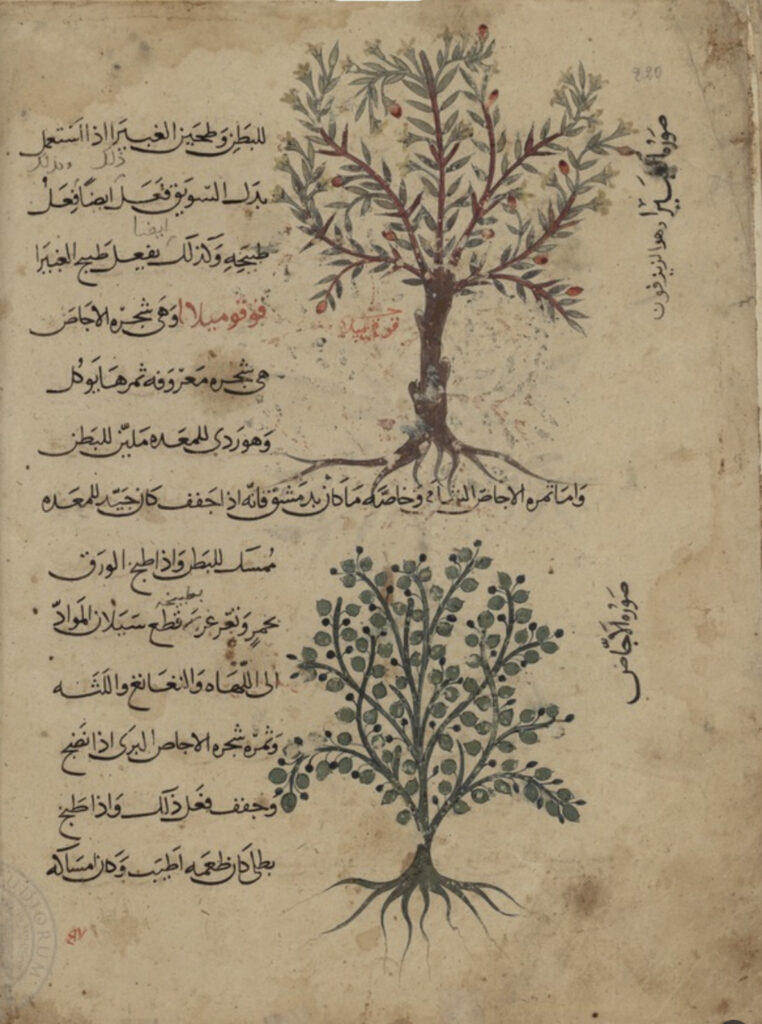

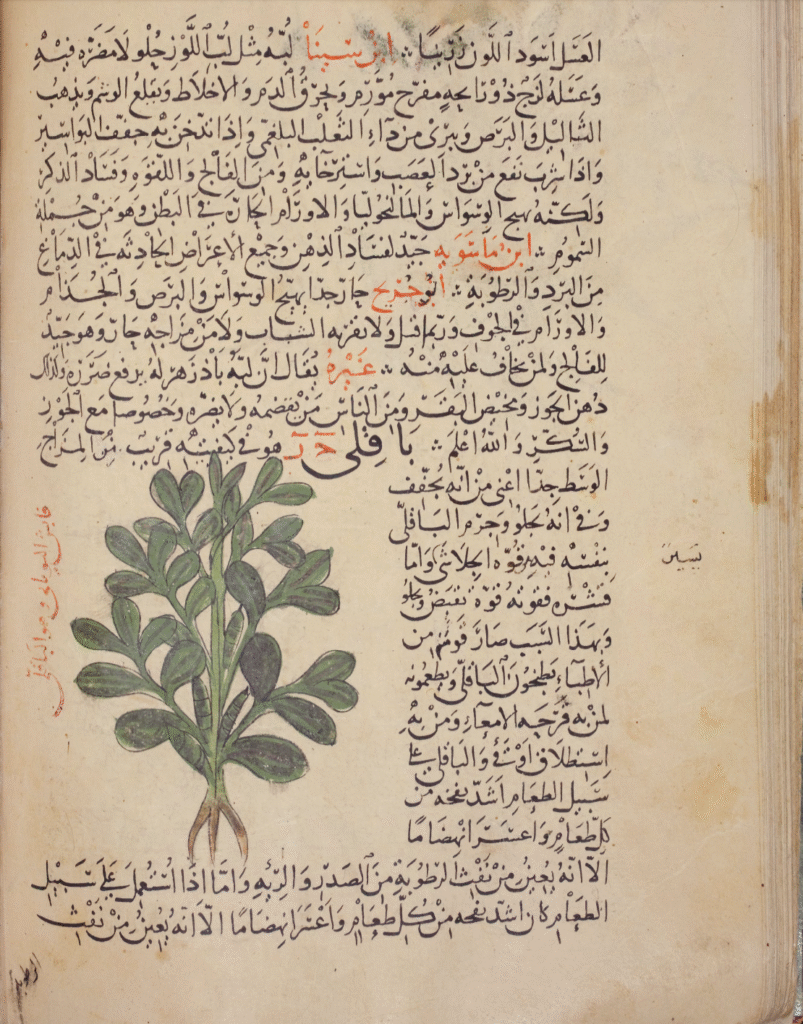

In Arabic, the mulberry was known as tūth (توث) or tūt (توت), the latter still being the term in modern Arabic. The word goes back to Assyrian tuttu (mulberry tree) but entered Arabic via the Aramaic tūtā. In Classical Arabic, it was also called firṣād (فرصاد), though this usually denoted the sweet mulberry. The blackberry (Rubus fruticosus) was known as tūth waḥshī (توت وحشي; ‘wild mulberry’) or ʿullayq (علّيق). In the literature, the white mulberry was often referred to as ‘sweet mulberry’ (توت حلو; tūt ḥulw), while the black variety was called ‘sour’ (حامض; ḥāmiḍ) or ‘Syrian (شامي; shāmī) mulberry.

In cooking, both the sweet and sour mulberries were used, in stews and beverages, and even in a judhaba (جوذابة) — where black mulberry juice was mixed with sugar. Dried unripe sour mulberries were used instead of sumac as a souring agent. Mulberries are only found in Middle Eastern recipe collections from Egypt, Iraq and Syria (whose mulberries were particularly prized), and appear not to have been used in Andalusi cuisine.

In the medical literature, sweet mulberries were thought to provide little nourishment to the body, be harmful to the stomach in that it corrupts its contents, as well as having laxative properties. Physicians recommended eating them before meals, and to take oxymel (sikanjabīn) afterwards.

Sour or Syrian mulberries, for their part, were said to cause constipation and colic, but beneficial for swellings in the mouth and throat, whereas the juice of its leaves was useful against tarantula bites..